Snacking on Banking and Insurance

A Spoon Full of 7x Value Makes the Medicine Go Down, and My Thoughts on Timing and Position Sizing

Disclaimer: By reading this article, you acknowledge and agree to the terms and conditions

Timing. Sizing. They have more to do with each other than you’d think.

What are the odds of “top-ticking” or “bottom-ticking” a name? Just look at the graph of cosine(x).

If you tried to “top-tick” cosine(x) on the way up at various points, good luck, nearly all of your attempts would end in tears. The same goes for trying to “catch a falling knife” on the downswing.

Individual stocks and the market as a whole follow a much more complicated regime than a simple cosine graph, but the one thing they share is that top-ticking and bottom-ticking is nearly impossible. My advice: don’t even try to do it.

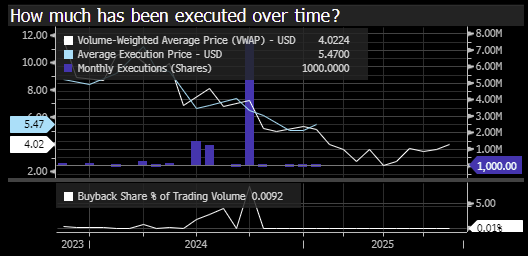

Frankly, it isn’t just traders who try, companies do it as well with share repurchases. Take Designer Brands, for example. In Q3 of 2024 they spent $50.6 Million (a massive amount relative to the market cap) repurchasing shares at $6.59, leaving roughly $20 Million in capacity remaining on the existing authorization. The repurchase screamed “bottom tick” attempt. Shortly afterwards, the stock dropped to $5.00 a share in Q4, $4.00 in 2025 Q1, and into the low 2’s in 2025 Q2, before recovering to the present $3.60 - $3.80 range. DBI’s repurchase activity since 2024 Q3? Essentially zero.

People angrily shake their fists “If you spent $50 Million buying it back in the 7’s you should love buying it back at $3!” It’s a good point.

But ask yourself, how many times have you done the exact same thing? You buy a position, it dips to a level even more attractive than your original entry, you don’t add, and a few months later you wish you did. For me, way more often than I’d like to admit.

That’s why I think timing and sizing have a lot to do with each other. Once you understand that the odds you have timed the “bottom-tick” are slim, starting with a smaller position and leaving yourself with room to add at more attractive levels can come in handy. The worst thing that can happen is the name runs away from you, and you make slightly less than you would have if you bought your entire position at once.

If I’m looking to make something a 3% position, I’ll start at a third of the desired weight, 1%, and buy another third of the desired position (1%) over the next 5 days. I’m not a large trader and it isn’t a matter of liquidity, rather, it prevents me from rushing in at a top or blowing out at a bottom and making emotionally charged decisions. If you look back to Google at the low 160’s earlier this year and Google at 320 currently, bullish / bearish sentiment entirely dominated a few trading days. Spreading your buys / sells over a few days reduces the likelihood of making drastic decisions at emotionally charged moments (of course, you can always make exceptions for moments driven by earnings, regulatory issues, etc).

I like to use the last third of my “firepower” to add at more attractive levels if the price moves against my entry, or add to my position at higher levels upon a breakout. This might sound counterintuitive; why save capital to buy more of something once it is already moving higher? The purpose of retaining the last third is to avoid “dead money”. Doing this gives you the option to add at more attractive prices, or establish a full position by adding at higher levels once a breakout begins; chances are once the breakout begins it has room to run.

In a market that is increasingly momentum driven, this tactic helps ensure your capital is deployed when the risk to reward is most favorable, not just when you first got excited about a trade. If you have a focus on smaller cap US Equities, or Global Value names that tend to float around until the breakout finally begins, saving a third of your firepower to add at more attractive levels, or upon a breakout, ensures you don’t tie up capital in a value trap.

Now, three trades I’ve been adding to recently.